Diata Abdullahi

From Alfred Hitchcock to Dorothy Arzner, the film industry has seen its share of both male and female giants. Regardless of era, women have been creating star-studded films for the silver screen alongside men, even outdoing them on multiple occasions. Almost lost to the annals of history, one female film-maker stood before the rest, Alice Guy-Blaché.

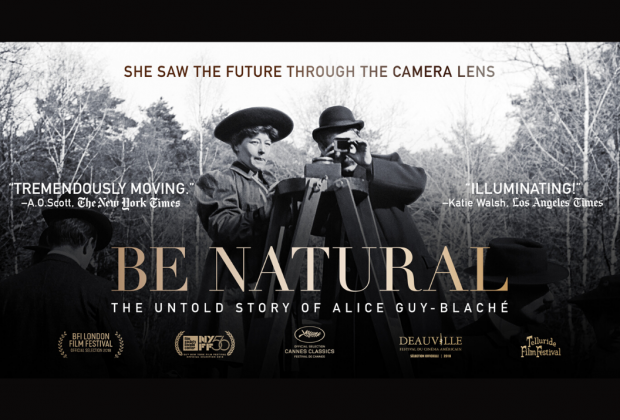

On September 26th, Professor Beth Baunoch displayed a biopic on the life of Alice Guy-Blaché. The event drew in a crowd of over fifty students and staff, with food and refreshments available to all.

As the professor of “Movies: History and Art,” Baunoch has been teaching about famous film-makers, including Alice Guy-Blaché for years. “When I first started here, in the film history textbooks there was about a paragraph about her…and that’s it,” she commented.

According to Professor Baunoch, the biopic was 10 years in the making, as the creators had to salvage different parts of Alice Guy-Blaché’s life and works from around the world. Parts of her legacy were preserved through her descendants and others through collectors.

The biopic itself seemed well-received by the audience. Covering Alice Guy-Blaché’s story from early life to her later years in America, it truly did justice to the story of one of films first giants. Narrated by Jodie Foster, “Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché” seemed to inspire its viewers with film creativity and ingenuity that Blaché herself would have appreciated.

Born in France, Alice Guy moved to Switzerland to live with her grandmother as a child. She went to a boarding school and later became the secretary under Leon Gaumont where she attended the first showing of the Lumiére Brothers Cinématographe, the first reliable way of displaying moving pictures.

Working with Gaumont, she pioneered a variety of directing and film-making techniques including synchronized sound, close-ups, and re-colorized film-making.

Under Gaumont, Blaché became the head of productions and either wrote, directed, or produced over a hundred of her own films, many of which have since been lost. Without her, Gaumont Film Company would not be what it is today.

Guy-Blaché eventually left Gaumont, creating her own film-making studio called Solax Films in New Jersey. As the founder and chairman, she created hundreds more films. These films covered all manner of genre from racial exposure to sexual freedom. It was unheard of at the time for a woman to not only direct, but also make films based on the sexual independence and liberation of other women while also using a cast made up of only African-American actors and actresses.

While owning her own studio, Guy-Blaché’s Solax Films flourished and grew, competing with other film studios such as Universal and MGM. Soon after, Thomas Edison drove many of these studios, including Solax Films, out of Fort Lee, NJ in to present-day Hollywood, California.

She then married a man named Herbert Blaché, a fellow film director and producer. Guy and Blaché had 2 children, Simone and Reginald. They took Simone everywhere they went, either on set or across the globe. Simone took care of the filmmaker in her later years.

After WWI & II, much of Guy-Blaché’s films were lost and destroyed. For decades, her husband Herbert took the credit for many of her films. She wouldn’t be properly accredited for her films until the mid-1980’s.

The biopic left a bad taste in the mouth of many of its viewers regarding the adversities Blaché faced. The Gaumont records completely expunged any of her involvements in its early founding out of sheer spite, and other film archives intentionally credited her husband Herbert for her films.

“What I enjoyed the most is the fact that she didn’t let that she was a woman and her age stop her from accomplishing what she wanted to do,” said Darian Jones, a Video Productions major at CCBC.

Guy-Blache’s story was an inspiration for everyone. The Crash of 1929 hit the film industry particularly hard, but she persevered and continued making films even when it was uncertain whether anyone watching would truly appreciate her art.

The end of the biopic described Guy-Blaché in her later years. She lived the rest of her life in New Jersey with her daughter Simone. It wasn’t until decades after her death in 1968 would the world come to know of the great impact Alice Guy-Blaché had.